The Covid 19 pandemic has significantly changed the way we live and work, accelerating the channel shift towards online services. However, there are 2 million households that struggle to afford internet access in the UK today, and 10 million adults lack the most basic digital skills. The Good Things Foundation, a UK-based non-profit, is working towards fixing the digital divide through research, advocacy, and community programs.

Emma Stone, Director of Evidence and Engagement at Good Things Foundation joins us to discuss barriers to digital inclusion, developing a minimum digital living standard, the economic returns of digital skilling, and more. Listen to the full interview below.

(00:00) In the Network Readiness Index 2022, the United Kingdom ranks 2nd in the Inclusion sub-pillar – however, room for improvement remains in areas like the gender gap in Internet use (where the UK ranks 38th) and the rural gap in use of digital payments (19th). How do cross-cutting barriers to digital inclusion, including access, skills, confidence, and motivation manifest across populations in ways that lead to exclusion?

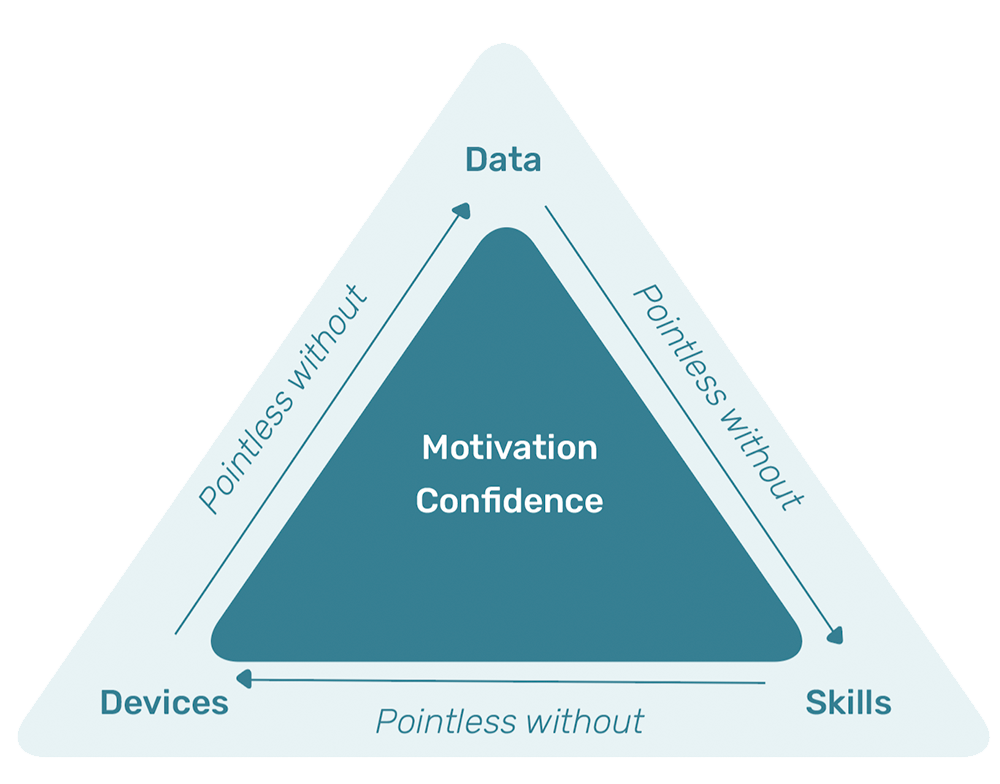

What we’ve learned from our research is that digital inclusion isn’t binary, where you are either included or excluded. It is really a spectrum of experiences. For some people, the primary barrier might be that they cannot afford internet connectivity or a suitable device. Whereas for others, their issue may be lack of skills, confidence or support. Data connectivity is pointless without a suitable device, which is pointless without the digital skills and competence, which is pointless without data connectivity. This is called the “pointless triangle”, which one of our Data Poverty Lab fellows developed.

Older age is still the strongest predictor of exclusion and limited use. However, barriers can manifest at all ages, particularly because there is a cost of living crisis going on at the moment in the UK and other parts of the world. That means we are seeing a rise in the number of people for whom internet access and use will be affected most by affordability. There might be other barriers around the device not being suitable and accessible in terms of reasonable adjustments, accessibility settings, or not being able to afford the extra kit that is needed for a disabled person to be able to use that device.

Another important point is that migrant status also brings a number of barriers. Refugees or asylum-seekers may not have the resources for acquiring data or devices. Language barriers can be a problem in terms of navigating online essential services, like government services. There can also be barriers in terms of levels of trust and confidence in how personal data will be used, and by whom. That can create added concerns about data privacy.

At a high level, we can see clear correlations between digital inequalities, and socioeconomic and health inequalities. But the reality is more nuanced than that, and it brings with it a spectrum of experiences.

(5:38) Good Things Foundation leads several programs aimed at enhancing digital inclusion. Your results show that these strategic initiatives, in tandem, work best for eliminating digital inclusion in a way that is sustainable and promotes longevity of digital participation. Can you tell us about the importance of a holistic approach to digital inclusion that reflects local needs?

The nuance point discussed above leads into the holistic approach to digital inclusion, and why you need to understand the whole package of support that someone might need in order to be digitally included. That links to research around the minimum digital living standard.

While it’s great that the UK is ranking so high in digital inclusion in the NRI, there is still a really clear level of digital inequality. We’ve been involved in a proof of concept feasibility study using something called the minimum income standard methodology. It’s a bottom-up approach to defining living standards. The team brought together digital inclusion experts to determine what should be in the minimum basket of digital goods for an acceptable standard of living for households in the UK. We’ve just published the findings of what a minimum digital living standard for households with children should look like. It includes everything from number of devices, level of devices, broadband, mobile data, essential skills, practical functional skills, and managing risk and harms. This is important because it reflects that holistic approach, and reflects what households themselves are saying is needed.

“A minimum digital standard of living includes, but is more than, having accessible internet, having adequate equipment, and the skills, knowledge and support people need. It is about being able to connect, communicate, and engage with opportunities safely, and with confidence.”

There is also an element of cultural norms involved, and the assumptions and expectations about how important it is to be online. Depending on where you are living in the world, being able to use the internet for your education is directly linked to its prevalence in a school child’s life, or in the interactions a parent has with their school around their children’s education.

Think about a household with disabled children or family members. What they need in order to meet their minimum digital standard might require additional support or equipment, but their basic needs are likely to be the same.

(17:25) Research shows that digital inclusion is not a fixed state – just as people can go from being digitally excluded to digitally included, the reverse can also be true. This trend was seen during the course of the COVID pandemic, and although our societies became more “digital”, the gap between those with and without essential digital skills actually widened. What factors may have contributed to this trend?

We have something called a Digital Nation, which is a way for us to use existing variable national datasets to give us a sense of where we’re at on digital inclusion. Within this I like to reference something called the Matthew effect, which is the sociological term behind the phrase “the rich get richer and the poor get poorer”. So with digital, what it means is that the more money you have, the better you can afford the unlimited data, the fast connectivity, the digital education, and the ability to use the Internet for work. The more money you have, the more opportunities open up for you. And even if you stay in one place status-wise, the digital world is progressing around you. The opportunities online are growing, and the gap between you and the ability to connect to health, education, essential information, and online learning is widening.

Regarding elderly populations, there are lots of different trends happening at the same time. If you are an older person living alone, then that makes it harder to get the support you need to be able to use the internet confidently. Data from Ofcom show that there are many people who are proxies, like family and friends, community organizations, or libraries who are providing that support. This is where measuring digital inclusion gets complicated, because sometimes you can see an increase in use of online services across older groups, but actually, some of that is being done with the help of other people, not independently.

Another big factor is fear of fraud, scams, and risks. What can help is face to face support, either from family members or from community organizations who are able to keep pace with the changes in digital technology. And of course, during the pandemic, some of those support systems were not available for people in the same way.

Another barrier we now face is that even terms like “digital native” can sometimes end up being unhelpful, because they compound assumptions. If you are 20 years old today, you may have a smartphone, or you may be an expert gamer, but that doesn’t mean you necessarily have the transferable digital skills and confidence to seek healthcare access online, or to be part of a remote or hybrid digital economy. COVID accelerated digitalization, and we risk making assumptions that everyone is now digitally included. Therefore, online services aren’t being designed in a way that takes into account those who may have lower literacy levels, who may face language barriers, who may run out of data halfway through their session, or someone who is only accessing the service on a mobile phone.

Part of what is brilliant about digital is that there is the opportunity for constant improvement, and responding to how people are using and interacting with platforms. However, even things that make platforms safer can become barriers, too. If two-factor authentication means I need this device and another device, that adds cost and complexity. “Inclusive by design” is a very important approach. How can you design more inclusively, and keep the threshold of entry as low as possible, to allow as many people as possible to confidently use your online services? This is an area where there is a lot of interest from government services and national health services. It’s more than website accessibility – it’s also about the usability of these tools.

(31:27) Last year, you commissioned a report with the Centre for Economics and Business Research around the economic impact of digital inclusion, which estimates a £9.48 return for every £1 invested in training persons to become more digitally able. Can you tell us a bit more about this report and its findings?

There are two things to highlight here. One is recognizing the value of these numbers, and being able to say that there is a return that comes from investing in the digital inclusion of citizens. Surfacing this helps to draw the link between an individual having the skills, confidence, and devices they need, and what that means for our economy and society.

This is a very conservative estimate of the value of digital inclusion to the digital economy. However, it doesn’t touch fully on things like the environment. There is one indicator there that we were able to gather data around, however we think there’s a much bigger and more complicated relationship between digital inclusion and environmental benefits, and economic benefits.

There’s also a frustration with the amount of data available at a sufficiently granular level. There’s an irony that despite all of the data that’s collected across the different parts of our lives, it’s not that easy to demonstrate a direct link between someone’s regular confident use of online services, and other areas of their lives. For example, health – we can see that there are correlations between the different indicators of health inequalities and digital inequalities, but there isn’t easy access to nationally available data about who is using things like the National Health Service app, and if there is a link between usage and health outcomes.

(38:15) While the actions of civil society organizations are critical for promoting digital inclusion and participation in the digital economy, policy intervention can also be a key driver of positive change when it comes to increasing access, affordability, and skills. What are some of Good Things Foundation’s key policy recommendations when it comes to enhancing digital inclusion?

One of our key policy recommendations is around leadership, and being able to set a clear definition for what digital inclusion looks like. In England, there hasn’t been a refresh on the digital inclusion strategy, and the last one was written in 2014. At the moment there is no clear ministerial leadership on this agenda. We want to see more commitment to cross-government work. Digital inclusion is and needs to be everyone’s problem, but nobody is really taking responsibility for it. Within the UK, some policy happens at the UK level, and some policy is devolved to the English government, Scottish government, and combined authorities. We need leadership at all different levels, and that is where things like the minimum digital living standard come in, because we need the government to adopt a clear benchmark which should be at the heart of strategy.

Another important point is recognizing that internet access is essential. With that come policy recommendations for ensuring that this is delivered, especially for those who are at most risk for not being able to get connected. We are also championing for not applying value added tax to broadband social tariffs. Most importantly, it should be the end customers who get the benefit of that reduction. We want to see internet access be genuinely affordable, especially for those who are in financial difficulty or low income.

Our policy ask around devices is finding a win-win between environmental benefit, and social value in fixing the digital divide. What we would like to see is large public sector organizations, government departments, and corporations taking the lead on this by looking at their unused tech devices and partnering with us so that those devices can be reused, repurposed, refurbished, and distributed to people for whom having a suitable device is a barrier. We’re piloting that at the moment, but our real ask is for the government to lead the way in thinking about the circular economy and how digital devices can be used for social good, as well as to reduce e-waste. There should not be devices going into landfills, when they could be repurposed.

Good Things Foundation is a registered charity based in the United Kingdom, the objective of which is to make the benefits of digital technology more accessible. It manages the Online Centres Network, the Learn My Way learning platform, and the National Databank. To learn more, visit https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org/

To learn more about the Network Readiness Index, visit https://networkreadinessindex.org/

Emma Stone is the Director of Evidence and Engagement at Good Things Foundation. Emma leads a team of specialist experts skilled in service design, user research, evaluation, data insights, marketing, communications, external affairs and advocacy. A social researcher by training, Emma has straddled research, policy and practice for two decades. Before joining Good Things Foundation in 2018, Emma worked at the Joseph Rowntree Foundation where she led the Policy and Research department, overseeing programmes on poverty, place, housing, aging, disability, race equality, and communities.